Is it McEwan who is thinking of Anglo-Saxon poetry here, or is it Adam? Adam often spends his solitary hours reading literature, and he develops a taste for poetry in particular. I felt flattered.”) But the Beowulf reference resurfaces more pointedly a few pages later, when Adam, after apologizing for breaking Charlie’s wrist, tells him smilingly, “the next time you reach for my kill switch, I’m more than happy to remove your arm entirely, at the ball and socket joint.”Ĭharlie describes this as Adam’s “first attempt at a joke,” but it’s a complex joke and a complex moment. (“I put my hand out to the boy and to my surprise he raised his and slotted his fingers between mine. Reading of Adam’s grip on Charlie’s wrist, most readers will recall, not Beowulf, but an earlier moment of significant hand-touching in the novel itself, when Charlie establishes an unexpected connection with a child on a playground. 1 The novel’s allusion to this moment is easy to miss.

Reaching out to seize and devour Beowulf, Grendel is stopped by “a handgrip harder than anything he had ever encountered in any man” and knows he has met his match sure enough, the hero kills Grendel by tearing his arm off at the shoulder. Charlie’s initial response, understandably, is to deny the possibility (“existentially, this is not your territory”), and he decides to reinforce his point in the simplest way possible-by reaching for Adam’s off button, or “kill switch.” Before he can, though, Adam grasps him by the wrist, and “the grip was ferocious.” It is not the declaration of love, then, but the hand-lock, tinged with beastliness by the unexpected word “ferocious,” that forces Charlie to recognize that he is dealing with a fellow life form, perhaps even a superior one.īut wait, haven’t we seen this before? At a climactic moment in Beowulf, the monster Grendel experiences an almost identical realization. A man newly in love knows what life is.” But that distinction begins to erode a few weeks later, when Adam reveals that he too has fallen in love with Miranda.

Gazing at his new purchase as it charges up for the first time and thinking of Miranda, the young woman upstairs whom he has recently fallen for, Charlie registers the ontological distance between himself and the android: Adam has “a semblance of breath, but not of life.

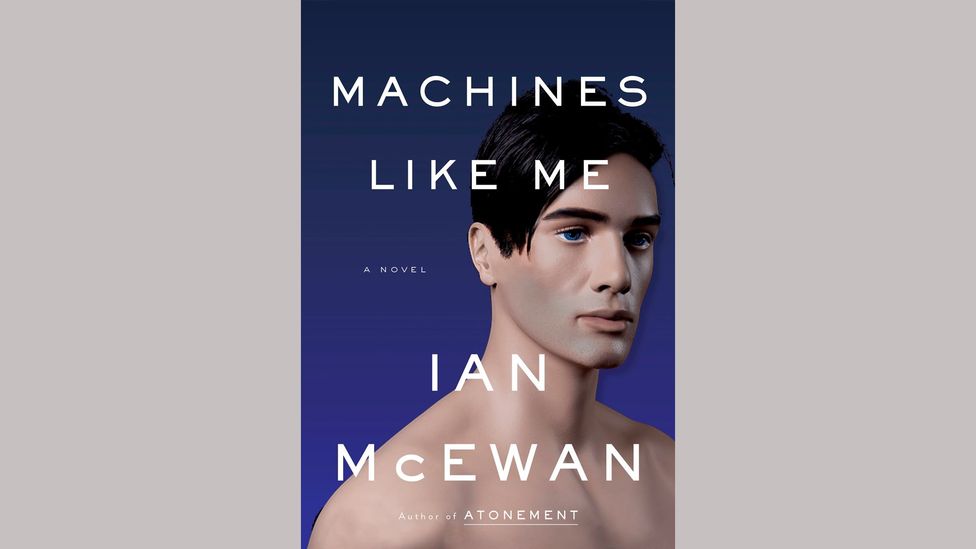

That moment is somewhat delayed in Machines Like Me, Ian McEwan’s new novel set in an alternative 1980s London, where the narrator, Charlie, has just purchased Adam, one of the first batch of truly lifelike artificial humans. In almost any book about artificial life, there comes a moment when the humans, like Victor Frankenstein, are obliged to confront the full reality of what they’ve created.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)